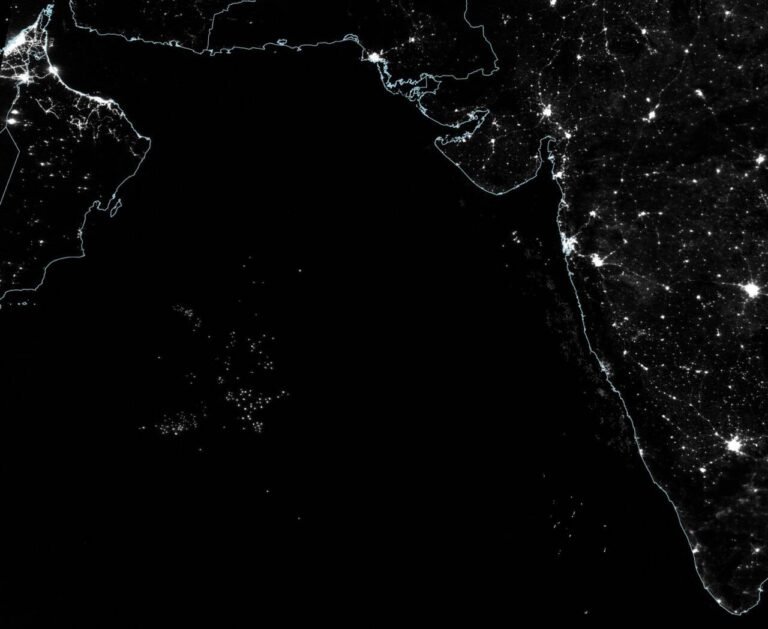

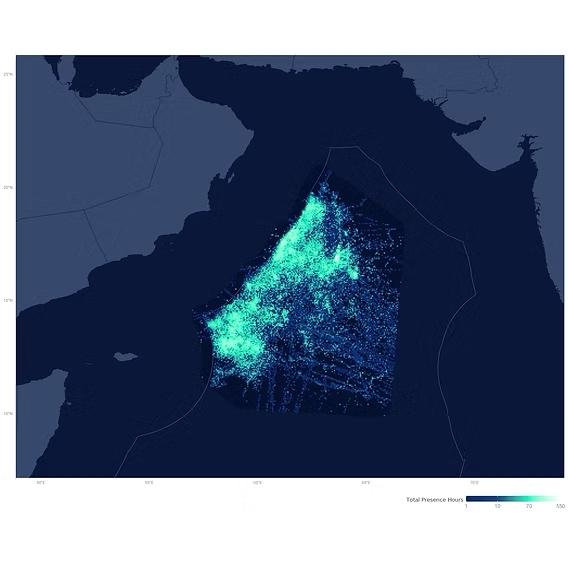

With each passing year, the number and intensity of these lights increase.

The fishing activity is taking place just outside the exclusive economic zones (EEZs) of India, Pakistan, Oman, and Yemen—technically legal, but entirely unregulated. These fleets, largely Chinese, are exploiting a regulatory gap, leading to the unchecked harvest of squid in the northwest Indian Ocean. The implications of this activity are vast, affecting biodiversity, regional economies, food security, and global sustainability efforts.

What Are Squid and Why Do They Matter?

Squid are cephalopods with soft, elongated bodies, large eyes, and ten limbs (eight arms and two tentacles). They are vital to marine ecosystems, serving as prey for sharks, whales, seabirds, and large fish like tuna. Squid have bilateral symmetry, a distinct head, and a chitinous internal skeleton. Though soft-bodied, their ecological importance is hard-hitting.

Squid fisheries support human consumption and supply fishmeal for aquaculture. But overfishing threatens their populations, which in turn jeopardizes marine food webs. Without squid, the predators that depend on them—from sperm whales to commercially valuable fish—face food shortages, potentially collapsing interconnected fisheries.

An Industrial Fishing Boom

Using satellite data, organizations like NASA, Global Fishing Watch, and Trygg Mat Tracking have mapped the explosion of fishing vessels in the Arabian Sea. These ships use high-intensity lights—sometimes more than 100 lamps per boat—to lure squid to the surface, where they are caught with nets and jigging lines. This technique creates vast constellations of light across the ocean, resembling cities from space.

Between 2015 and 2019, the number of vessels in the region increased from about 30 to nearly 300. The fishing season, initially limited to November through January, now stretches from September to May. Most vessels leave only during the monsoon season.

The recent analysis revealed a troubling twist: these vessels are not using traditional jigging methods but newer, less selective net gear. This has led to significant bycatch, including tuna and other species not authorized for harvest—further compounding the ecological damage.

Ecological Impacts

-

Overfishing depletes squid stocks faster than they can reproduce.

-

Bycatch results in the unintended capture of non-target species like tuna.

-

Habitat damage occurs from destructive gear that disturbs seamounts and coral habitats.

-

Food chain disruption weakens populations of predators that rely on squid.

-

Biodiversity loss may follow as ecosystems destabilize.

These environmental issues are exacerbated by a lack of accountability and transparency in industrial fishing operations, particularly in international waters.

Economic and Social Impacts

Local fishing communities across India, Pakistan, Oman, and eastern Africa are at risk. These communities rely on small-scale, traditional fishing practices that cannot compete with industrial fleets. Key economic concerns include:

-

Loss of income for small-scale fishers

-

Decreased local catch due to competition and stock depletion

-

Unfair trade advantages benefiting foreign corporations

-

Widening inequality between industrial fleets and local communities

Furthermore, labor concerns have been raised, including poor working conditions and potential exploitation aboard industrial vessels.

Regulatory and Geopolitical Vacuum

This fishery operates in a legal gray zone:

-

It falls outside the Southern Indian Ocean Fisheries Agreement (SIOFA) and beyond the Indian Ocean Tuna Commission’s (IOTC) species mandate.

-

China, the flag and port state of the majority fleet, holds most of the operational data and bears key responsibility.

-

There is no enforceable regional framework for squid fisheries in this part of the Indian Ocean.

-

Automatic Identification Systems (AIS) and Vessel Monitoring Systems (VMS) help track ships, but many vessels disable these systems.

As a result, monitoring, control, and enforcement (MCS) efforts are limited, allowing unregulated activities to continue unchecked.

Connecting to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

The Chinese industrial squid fishery undermines several UN SDGs:

-

SDG 14: Life Below Water – Overfishing and habitat degradation threaten ocean biodiversity and health.

-

SDG 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth – Local fisheries lose jobs and income; labor abuses may occur on industrial vessels.

-

SDG 12: Responsible Consumption and Production – Unsustainable harvest practices deplete resources and reduce long-term yields.

-

SDG 17: Partnerships for the Goals – A lack of international cooperation weakens responses to shared marine challenges.

Solutions and Policy Recommendations

A sustainable and equitable response to the unregulated squid fishery in the northwest Indian Ocean requires coordinated action at multiple levels:

Regulatory Measures:

Establish a regional governance framework under SIOFA or a new treaty. Enforce science-based catch limits, seasonal closures, and stricter monitoring through satellites and independent observers.

Industry Reforms:

Promote eco-certification (e.g., MSC), require selective gear to reduce bycatch, and mandate digital tracking for full catch traceability.

Policy Leadership:

China must enhance transparency and share data. Coastal developing nations should strengthen domestic regulations, while global organizations like the FAO and IUCN must foster international cooperation.

Community Engagement:

Support local co-management, train small-scale fishers in sustainable practices, and increase consumer awareness of responsible seafood.

Technology and Monitoring:

Use VIIRS satellite data to detect unregulated fleets, expand AIS/VMS mandates, and apply AI tools for real-time monitoring and enforcement.

How You can Help

At Wild at Life, we are committed to protecting our oceans and the communities that depend on them. But we cannot do this alone. Without collective action, stronger regulations, and support from partners, governments, and the public, the damage will continue unchecked. Together, we can shine a light on this crisis — and turn awareness into lasting change.